On paper, sales quotas and commissions look perfectly reasonable. You want growth, so you set a target. You want motivation, so you tie money to the target. The spreadsheet glows with projected revenue.

W. Edwards Deming saw the trap. He warned that when leaders rely on numerical goals and incentives instead of leadership and system design, people will do exactly what you pay them to do—even if it quietly harms customers, coworkers, and the long-term business. Quotas, he argued, invite distortion and fear rather than learning and improvement.

This article explores how that plays out in a mid-sized manufacturing company and how one leadership team used Deming’s ideas to redesign their sales system. The punchline: removing traditional quotas and commissions didn’t make the sales team soft. It made the whole company stronger—and gave them a competitive advantage their rivals couldn’t easily copy.

A sales engine that looked great on paper

Maria was the CEO of a mid-sized manufacturer of machined components for industrial equipment. Tom led sales. Their model was familiar and, at first glance, sensible: annual sales quotas by territory, rich individual commissions, and a flashy “Top Gun” trophy for the top performer every quarter. On the conference-room whiteboard, the plan looked clean. Each year, quotas climbed. Stretch goals triggered bigger bonuses. The trophy promised bragging rights and status.

But the story on the shop floor felt very different.

By the third week of every month, the plant lurched into firefighting mode. Orders flooded in at the end of the quarter as reps scrambled to “make their number.” Customers had been promised delivery dates the factory could not reliably meet and discounts that operations had never signed off on. Forecasts swung wildly and were rarely believed. Overtime spiked. So did stress. Inside the business, an odd phrase kept popping up in meetings: “We’re winning deals, but we’re losing money.”

One Thursday afternoon, Maria finally pulled Tom into her office. “Everywhere I go,” she said, “I hear the same complaint: we’re growing, but we’re exhausted and margins are shrinking. What is going on?”

Tom sighed. “We are winning deals,” he said, “but operations is overwhelmed. The reps will agree to almost anything to hit quota. But if we take away quotas and commissions, how do I keep them hungry?”

It was an honest question—and a common one.

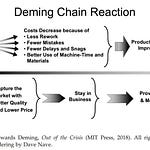

What Deming saw in quotas and numerical goals

Deming’s answer begins with a simple observation: most of the performance of a system comes from the system itself, not from individual effort. Sales results are shaped by pricing, product fit, lead times, available capacity, reputation, and dozens of other factors outside a salesperson’s direct control. When leaders pretend otherwise, they push variation and frustration into the organization.

Deming argued that numerical goals and quotas create three predictable patterns:

Distortion of the system. People learn to game the metrics—pulling orders forward, discounting aggressively, or pushing the wrong products—because their pay depends on it.

Fear and short-termism. When missing a number threatens income or status, people naturally become defensive and cautious. They protect themselves, not the system.

Sub-optimization. Individuals or departments “win” while the company loses. Sales hits its quota while operations burns out and customers get unreliable service.

In Deming’s view, the proper role of management is not to demand higher numbers but to work on the system so that good results are the natural outcome. “Substitute leadership,” he urged, in place of quotas and numerical goals. That means understanding how work actually flows, designing stable processes, and helping people collaborate instead of compete.

Eliminate management by objective.

Eliminate management by numbers, numerical goals.

Substitute leadership.

— W. Edwards Deming

Maria had bumped into exactly the pattern Deming described. Her sales plan was producing visible wins on the scoreboard and invisible damage everywhere else.

Mapping the real sales system

After that Thursday meeting, Maria didn’t rush to rewrite the compensation plan. Instead, she changed her question. Rather than asking, “How do we motivate salespeople?” she asked, “What is the system of sales here?”

She sat in on customer visits. She listened to calls. She walked the plant during those painful end-of-month spikes. She talked with customer service about complaints and cancellations.

A few themes emerged:

Reps offered deep discounts at the end of each month to close deals and hit quota.

They promised lead times and configurations that were easiest to sell, not necessarily what the factory could deliver reliably or what was best for the customer’s long-term performance.

Early-month activity was relatively quiet; then everything surged at the end of the reporting period.

Forecasts were treated as fiction by operations because they were routinely blown apart by last-minute deals.

The compensation plan, Maria realized, had become a machine for converting fear into distorted orders. The more pressure they applied to hit the number, the more chaos they created downstream.

One evening, Tom found Maria in a small conference room, staring at a wall covered in charts: margins by order, rush charges, late deliveries, rework, and customer churn. “So… you’re really thinking about changing comp,” he said.

“I’m thinking about changing the system,” Maria replied. “Deming says the job of management is to work on the system, not just motivate people. Right now, our system pays people to create chaos.”

For Tom, it was a disorienting moment. But he couldn’t deny the data on the wall.

Redesigning sales to support the whole system

Rather than retreating to a closed-door executive session, Maria and Tom formed a small cross-functional team: sales, operations, finance, and service. The question in front of them was straightforward but radical: How could they design the sales system so that the easiest way to earn a good living was to do the right thing for the customer and for the company’s long-term health?

Over several working sessions, they made three major changes.

1. Shift from individual quotas to shared aims

They eliminated individual sales quotas. Instead of each rep chasing a personal number, the company adopted a small set of shared aims:

Profitable growth at the company level.

Smoother flow of orders across the month and quarter.

Higher retention of the right customers—the ones who valued reliability and partnership.

This didn’t mean sales stopped measuring anything. It meant they stopped treating individual quota attainment as the ultimate scoreboard. The new focus was on whether the business as a whole was getting healthier.

2. Shift from spiky commissions to stable income

Next, they changed compensation. The old plan featured aggressive commissions that swung income dramatically from month to month. The new design paid a solid base salary, with a smaller, shared bonus tied to overall results and customer experience.

The intent was not to punish top performers, but to remove fear. Reps would no longer have to choose between telling a difficult truth and paying their mortgage. Income would be stable enough that they could focus on long-term relationships.

In a rollout meeting, Tom voiced the question hanging over the room. “If there’s no personal quota,” he asked, “what does a ‘good month’ look like for a rep?”

Maria answered, “A good month is when you help customers choose the right work, when you place orders early enough that we can build smoothly, and when we all win—customers, the plant, and you. The bonus will follow that, not just the last-minute number on a chart.”

3. Shift from volume obsession to system health

Finally, they changed what they paid attention to. Instead of obsessing over monthly volume by rep, they reviewed:

On-time delivery and schedule adherence.

Reorder rates and customer retention.

The accuracy and usefulness of forecasts.

Simple signals of customer trust: Would this customer gladly buy from us again?

These measures told a more honest story about the health of the system. They were harder to game and more closely tied to the company’s long-term survival.

No number of successes in short-term problems will ensure long-term success.

— W. Edwards Deming

What changed—and what didn’t

The first quarter under the new system felt strange. The usual end-of-month spike flattened out. Forecasts were still imperfect, but they were close enough that the plant could plan with more confidence. The infamous 2 a.m. Saturday fire drills almost disappeared.

Reps behaved differently too. Without the pressure of individual quotas, they started saying things they had never dared to say before: “This configuration isn’t right for you. It may be cheaper now, but it will cost you in downtime. Let’s look at a better fit.” They brought operations into big opportunities earlier. They walked away from deals that looked impressive on a scoreboard but would have been unprofitable or destabilizing once they hit the factory.

After six months, the numbers told a quieter, healthier story. Revenue had grown modestly. Profit had grown faster. Warranty claims and rush charges had dropped. Two key customers who had quietly been shopping for alternatives after a string of late orders renewed multi-year agreements.

What hadn’t changed was the basic character of the sales team. The people were the same. Their desire to win was the same. What changed was the system around them—the aim of their work, the way they were paid, and the signals leadership chose to emphasize.

Deming’s insight was playing out in real life: when you change the system, behavior follows.

Actionable takeaways for your business

You don’t have to copy Maria’s plan exactly to benefit from the same thinking. Here are a few steps you can take in your own organization:

Map your real sales system. Follow a few opportunities from first contact through delivery and support. Where do quotas and incentives distort decisions? Where do they create fear or hide problems?

Ask where sub-optimization is happening. Are there places where sales “wins” while operations, service, or customers clearly lose? Name those honestly.

Experiment with shared aims. Try shifting one team from individual quotas to shared targets tied to company-level performance and customer experience.

Stabilize income before you change behavior. If you want reps to act long-term, give them an income structure that doesn’t punish them for doing so.

Change what you talk about. In sales meetings, spend at least as much time on forecast quality, delivery reliability, and customer retention as you do on this month’s number.

Start small: one team, one product line, one experiment. Measure what happens to system-level outcomes, not just individual leaderboards.

A competitive advantage

Most of your competitors are still trapped in the same cycle Maria started in: set higher quotas, dangle bigger commissions, push people harder, then scramble to cope with the side effects. It’s familiar. It feels decisive. And it quietly erodes trust and stability.

Choosing a Deming-inspired path takes more courage. It asks you to believe that people want to do good work and that your job as a leader is to design a system that lets them. It asks you to trade a bit of short-term drama for long-term strength.

But that choice is exactly where the competitive advantage lies.

A calm, predictable, trustworthy sales system becomes a differentiator customers can feel. It reduces internal friction, frees up capacity for real improvement, and makes your promises more reliable. In a market full of quarter-end gimmicks and disappearing discounts, being the company that tells the truth and delivers consistently is a powerful position.

Bringing it home

If you recognize pieces of Maria and Tom’s story in your own business, you are not alone. Many leaders have inherited quota-driven systems that once seemed cutting-edge and now feel misaligned with the realities of modern manufacturing.

But you don’t have to burn everything down. Start with one honest question: What is my sales system teaching people to do? Is it encouraging collaboration across departments or pitting colleagues against each other? Is it reinforcing long-term relationships with customers or training them to wait for desperate end-of-month deals?

From there, take one step toward Deming’s challenge to “substitute leadership” for numerical goals. Work on the system. Make it easier for people to do the right thing the first time.

The job of management is not supervision, but leadership.

— W. Edwards Deming

At the end of the day, quotas and commissions are tools, not destiny. You get to choose whether they drive your company into constant firefighting—or whether you design something better.

And if you do, you may find what Maria and Tom found: your people didn’t need more pressure. They needed a system worthy of their effort.