Public recognition is one of the most familiar tools leaders use to motivate people. It feels generous. It feels human. It feels like an easy way to say, “This matters here.”

But recognition is never just a moment of appreciation. It is a signal that lingers. Over time, it teaches people what the organization truly values, what kind of work is safest to pursue, and what quietly carries risk.

In interdependent work—where outcomes are shaped by systems, not individuals—that lesson compounds. Recognition keeps teaching long after the applause fades.

Recognition is a system choice

Most leaders don’t design awards because they enjoy competition. They do it to build energy, reinforce values, and show that effort is noticed. Public recognition feels like a low-cost, low-risk way to encourage performance.

What often goes unexamined is how recognition behaves inside a system. When awards are scarce and visible, they begin to function like ranking—even when leaders explicitly reject that intent. People adapt quickly. They gravitate toward work that gets attention. They protect credit. They deprioritize work that is essential but less visible, such as mentoring, prevention, and improving methods.

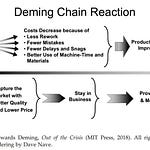

W. Edwards Deming urged leaders to look past intentions and examine effects. His concern was not appreciation itself, but the habit of confusing outcomes with merit in environments where outcomes are shaped largely by the system. When leaders reward results without studying the conditions that produced them, they unintentionally teach people to manage visibility instead of improving the work.

To see how this dynamic unfolds—and how it can be redirected—consider what happened inside one professional services firm.

When recognition becomes ranking

Brightline Advisory is a mid-sized professional services firm whose work depends on collaboration, shared methods, and careful coordination across teams. After a demanding year marked by heavy workload and rising attrition, leadership introduced a monthly public recognition program called Bright Star. Each month, one individual would be publicly celebrated for strong performance.

At first, the program landed exactly as intended. People appreciated the acknowledgment. Leaders felt they were reinforcing the right behaviors. Over time, however, the meaning of the recognition began to change—not because anyone altered the rules, but because the system itself was teaching a lesson. Sarah, who led one of the delivery groups, noticed the shift before it showed up in reports or metrics. She brought her concerns to Tom, a managing partner.

“At first people seemed energized,” she said. “But after a while, something shifted—and not in a good way.”

She wasn’t describing morale problems. She was describing how work was unfolding. Knowledge sharing slowed. Junior consultants hesitated to ask for help. Conversations about who would present results grew tense. Work that attracted attention felt safer than work that prevented future problems.

Tom kept returning to intent. “We weren’t trying to rank anyone,” he said. “We just wanted to acknowledge great work.”

“I know,” Sarah replied. “That’s what makes this tricky. It lifted up a few—and it changed what everyone else feels they have to do to be seen.”

Nothing in Bright Star instructed people to compete. But recognition was scarce and highly visible. In an interdependent system, that combination quietly invites comparison. People adjust their behavior to the signal, not the slogan.

Deming warned leaders about this pattern. “Abolish ranking and the merit system,” he wrote. In its place, he urged leaders to “manage the whole company as a system.” What follows from ranking is not better performance, but predictable distortion.

Abolish ranking and the merit system.

Manage the whole company as a system.

— W. Edwards Deming

As months passed, leaders began to see what Sarah had been describing. Certain projects drew disproportionate attention. Riskier work was avoided. Helping another team felt like a tradeoff against personal visibility.

The conversation changed when leadership stopped debating whether Bright Star was motivating and asked a different question: What is this recognition teaching people to do? That question slowed things down. Instead of choosing winners more carefully, leaders began studying variation—project mix, timing, staffing, and handoffs. They began to see that Bright Star rewarded outcomes without improving the system that produced those outcomes.

Only then did the solution emerge. The monthly award was retired. In its place, teams began sharing what they were learning: improvements to methods, prevention practices, and collaboration. Recognition shifted away from status and toward understanding how good work was produced.

Over time, the effects became visible. Knowledge moved more freely. Cooperation increased. Results stabilized—not through competition or heroics, but through better system design. As Deming put it, leaders must “remove barriers that rob people … of their right to pride of workmanship.”

Remove barriers that rob people … of their right to pride of workmanship.

— W. Edwards Deming

Where managers often get tripped up

When we look at stories like this, it’s tempting to say the original recognition program was “wrong.” That framing isn’t very helpful.

What usually happens is that we underestimate how powerful recognition really is. We treat it as encouragement rather than as system design. We assume people will hear praise as appreciation, not as instruction.

In interdependent work, people are constantly scanning for signals about what is safe, what is valued, and what advances their standing. When recognition is scarce and public, it inevitably creates comparison—even if we never use the language of rank.

We also tend to over-attribute results to individuals. When outcomes look good, we reward the visible contributor without asking how much of that outcome was shaped by project mix, timing, staffing, or client behavior. That makes recognition feel fair in the moment while quietly distorting behavior over time.

None of this comes from bad intent. It comes from managing people instead of managing the system they work in. Deming’s reminder was simple and uncomfortable: most performance belongs to the system. Recognition that ignores that reality will eventually work against us.

Actionable takeaways

So how can leaders design recognition that strengthens the system instead of distorting it?

Map your recognition ecosystem. Examine all forms of recognition—formal and informal—and ask what behaviors they encourage, and what they crowd out.

Separate appreciation from ranking. Express gratitude freely, but avoid designs that create winners and losers in interdependent work.

Recognize methods, not just outcomes. Highlight prevention, mentoring, improved handoffs, and practices others can reuse.

Treat results as inputs for study. When outcomes are strong, ask “By what method?” and spread that learning without attaching status.

Design for pride of workmanship. Invest in systems that make good work the norm, not something that requires heroics to achieve.

When recognition works this way, it becomes part of how the organization learns and improves.

Closing

Awards feel generous. Public praise feels motivating. That is exactly why leaders need to treat recognition as a system choice, not a gesture.

In interdependent work, recognition can strengthen cooperation or quietly undermine it. When leaders align recognition with learning and system improvement, appreciation becomes more than applause—it becomes a foundation for lasting performance.