Every organization—whether a small consultancy or a global enterprise—is a web of interdependent parts. Yet most are managed as if each department, team, or individual were a separate machine to be tuned in isolation. Targets are set, bonuses awarded, and dashboards celebrated—all without asking how those local victories affect the system as a whole. W. Edwards Deming warned that this “sub-optimization” is one of management’s most costly blind spots: the parts can perform beautifully while the enterprise itself underperforms. To see what this looks like in practice—and how to escape it—consider the story of a professional services firm that learned the hard way that optimizing individual parts can quietly destroy the whole.

When every team wins—and the company loses

At a growing professional services firm—busy, modern, and full of smart people—something didn’t add up. Each department was celebrating its own success. Operations had reduced delivery time by 25 percent, and the sales team had exceeded its revenue targets. On paper, things looked great. Yet, customers were increasingly dissatisfied. Complaints about rushed projects, inconsistent service, and miscommunication were rising. Internally, tension brewed between departments.

The operations manager, Marcus, pointed to his metrics. “We’ve hit every efficiency target,” he said. The client services lead, Lila, countered that customer satisfaction was slipping. The sales director, Tom, defended his team: “Our job is to bring in business. Maybe operations needs to adjust.” Each spoke with conviction, each confident they were doing their job well.

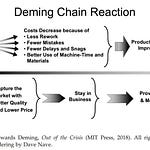

But as Deming explained, the performance of any part or person in an organization can only be understood in terms of its contribution to the system’s overall aim. In other words, when departments pursue their own metrics without understanding how their work affects the rest of the organization, they may be “winning” locally while the company loses as a whole.

Deming warned that “Left to themselves, components become selfish, competitive, independent profit centers, and thus destroy the system.” He defined a system as “a network of interdependent components that work together to accomplish the aim of the system.” Each part of an organization—sales, operations, finance, customer support—relies on the others. Success requires harmony, not competition.

Left to themselves, components become selfish, competitive, independent profit centers, and thus destroy the system.

— W. Edwards Deming

Seeing the process to improve it

At the firm, the realization came slowly. The leadership team began to map how work actually flowed from one department to another. Sales commitments became project delivery constraints. Delivery schedules shaped customer satisfaction. Customer feedback influenced sales renewals. For the first time, everyone could see that their work didn’t exist in isolation. Deming once noted, “If people do not see the process, they cannot improve it.”

If people do not see the process, they cannot improve it. — W. Edwards Deming

Once the team visualized their interdependencies, conversations shifted from blame to curiosity. They began asking, “What is the aim of our entire system?” rather than “How can my team hit its number?” Together, they agreed that the true aim was not merely to increase short-term output or revenue, but to deliver reliable, high-quality service that built long-term relationships.

Transforming through cooperation

With this shared aim, they adjusted their incentives and measures. Sales began setting expectations based on delivery capacity, not just closing speed. Operations shifted from rushing projects to focusing on consistency and quality. Client services joined early in the process to anticipate customer needs before issues arose.

Six months later, the firm’s revenue per client had grown by nearly twenty percent, but the deeper transformation was cultural. Complaints dropped sharply. Referrals increased. Employees reported less frustration and more pride in their work. As Marcus put it, “We didn’t work harder—we just stopped working against each other.”

Managing the system, not the people

Deming famously said, “A system must be managed. It will not manage itself.” Systems do not improve through pressure or exhortation, but through understanding and design. When leaders focus only on optimizing subsystems—each department, team, or metric—they unintentionally sub-optimize the whole. True improvement requires managing interdependence, not independence.

The lesson is timeless and universal: when a business, school, or agency learns to see itself as one system with a shared aim, performance improves naturally. The parts no longer compete; they collaborate. And the result is not just better numbers, but greater stability, learning, and joy in work.

Actionable Takeaways

Draw the system. Create a simple flow diagram showing how work moves across departments. Clarity reveals waste, rework, and misalignment.

Redefine success. Evaluate each team’s performance by how it contributes to the organization’s overall aim, not by isolated metrics.

Remove local targets that conflict with the system. If a goal drives one group to optimize at the expense of others, it’s the wrong goal.

Foster cooperation over competition. Encourage departments to solve problems together rather than negotiate boundaries.

Lead with purpose. The role of management is to optimize the whole system—helping every component work together for customers, employees, and the organization’s future.

When an organization learns to see itself as one system, improvement becomes continuous and sustainable. That, Deming would remind us, is not just better management—it’s a competitive advantage.

A system must be managed. It will not manage itself. — W. Edwards Deming