Fear is expensive.

It doesn’t appear on financial statements, but it shows up everywhere else—late reporting, hidden problems, padded numbers, quiet compliance, and people doing just enough to stay out of trouble. W. Edwards Deming captured the effect in a single line: “Fear invites wrong figures.” When fear is present, organizations don’t see reality clearly, because reality feels unsafe to report.

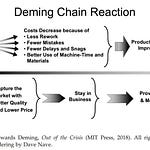

Many leaders treat fear as a cultural or interpersonal issue. Deming did not. In Out of the Crisis, he was explicit: “Drive out fear, so that everyone may work effectively for the company.” He described fear as a management problem—created, reinforced, and sustained by the way the system is designed. Until fear is addressed at the system level, improvement efforts may stall, no matter how capable or well‑intentioned the people involved may be.

Drive out fear, so that everyone may work effectively for the company.

— W. Edwards Deming

Fear is rational—and systemic

People don’t hide problems because they lack integrity. They hide problems because the system has taught them what happens when they speak up. Fear is rational. When the cost of surfacing a problem is higher than the cost of hiding it, people adapt. They delay. They soften the message. They adjust the numbers. Over time, the organization becomes exactly as honest as the system allows it to be.

This is why Deming warned that many of the most important figures managers need are unknown or unknowable. When fear governs behavior, the data itself becomes unreliable—not because people are dishonest, but because honesty feels dangerous.

A familiar pattern

Consider an organization running behind schedule. Elena, a frontline operator, notices a subtle change in how a process is behaving. Nothing dramatic. Output is still within spec. But something feels off. Stopping the process might turn out to be unnecessary—and attract criticism. Letting it run might result in scrap or rework later. Either way, the risk feels personal.

“If I stop it and nothing’s wrong, I’ll get blamed,” she thinks. “If I don’t stop it and it fails, I’ll get blamed worse.” So the process keeps running.

Hours later, failure occurs. Scrap spikes. Downtime stretches longer than it would have if the issue had been addressed earlier. Later, James, a senior leader, asks why no one spoke up sooner.

“Why didn’t we hear about this earlier?” he asks. The answer is predictable: people have been burned before.

This isn’t a failure of motivation or training. It’s a predictable outcome of the system: people do what keeps them safe. Deming warned that fear suppresses information long before it shows up as failure, because people learn to survive within the system they are given.

What changes when fear is removed

Now imagine a different response.

James changes the way he responds when problems surface. Instead of asking who made the wrong call, James asks what signals were present and how the system made responding risky.

“Where did the first signal show up,” James asks, “and what did we make risky about acting on it?” They make it explicit, then demonstrate through their actions, that surfacing problems early will not be punished.

The next time a similar signal appears, the process stops sooner. The issue is confirmed. Downtime is brief. Loss is limited. Nothing changed about the equipment. Nothing changed about the people. What changed was the risk calculation in their heads.

When the system punished early signals, those signals disappeared. When the system protected early signals, learning sped up. As Deming cautioned, without trust, people cannot work together to improve the system, no matter how skilled they are.

Fear as a competitive issue

This is where fear stops being a cultural concern and becomes a strategic one. Organizations that surface problems early learn faster than organizations that hide them. Over time, speed of learning—not size, not technology, not even experience—becomes the real competitive advantage.

Teams that operate without fear adapt faster, recover sooner, and avoid repeating the same mistakes. That advantage compounds quietly but relentlessly, because competitors can copy tools and processes, but they struggle to copy systems that consistently tell the truth.

Here’s how you can eliminate fear

Driving out fear does not require grand programs or slogans. It requires consistent management behavior, especially in moments when problems surface.

Establish a non‑punitive escalation rule.

Make it explicit that surfacing a problem early will never be punished. Write it down. Repeat it often. Most importantly, enforce it through your reactions when bad news appears.Change the first question leaders ask.

Replace “Who did this?” with “What in the system made this likely?” The first sentence out of a leader’s mouth teaches everyone what is safe.Use a simple learning review after problems occur.

After any defect, delay, or stoppage, ask what signal appeared, what decision was made, and what the system made easy or hard in that moment.

A simple daily learning review captures what abnormality was observed, when the earliest signal appeared, what risk people perceived at the time, and what will be changed so the right action feels safe next time.

The point of driving out fear

Fear doesn’t disappear because leaders say the right words. It disappears when people see—again and again—that telling the truth is safer than hiding it.

In every organization, improvement begins as a small signal: a question, a hesitation, a quiet sense that something isn’t quite right. When fear is present, those signals are swallowed. When fear is removed, they become the starting point for learning.

Driving out fear isn’t about being kind or permissive. It’s about creating the conditions where people can contribute what they actually know, not just what feels safe to say. It’s about shifting energy away from self‑protection and toward shared purpose.

Fear is a management choice, whether intentional or not—and so is its absence. Deming was clear that fear undermines pride of workmanship, because people cannot take pride in work they are afraid to speak honestly about. When fear governs, people brace themselves and problems arrive late. When fear is driven out, people speak sooner, learn faster, and take pride in getting things right.

That is the point of driving out fear. It’s the moment when people stop bracing themselves and start bringing their whole selves to the work—and when improvement stops being forced and starts becoming something people believe in.

All anyone asks for is a chance to work with pride.

— W. Edwards Deming