Every December, leadership teams gather around spreadsheets and planning decks, and one thing slowly crowds out all the others: next year’s growth target. Ten percent. Twenty. “Double in two years.” The number starts to feel powerful, almost magical—as if declaring it clearly enough, and repeating it often enough, will somehow bend the organization into making it true.

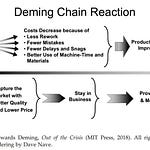

But saying a number out loud does not change the future. A number can only describe what already happened. If an organization wants different results next year, it has to change what produces results in the first place. It has to change the system.

W. Edwards Deming gave us a simple place to start: “A system must have an aim. Without an aim, there is no system.” Growth targets can be energizing, but without an aim they become detached from purpose, values, and tradeoffs. Deming paired that idea with an equally blunt warning: “A numerical goal accomplishes nothing. Only the method is important, not the goal.” Deming was not opposed to bold goals; he was opposed to pretending that boldness alone could change outcomes.

Healthy end‑of‑year planning holds both truths at once. The aim sets direction. The method creates learning. Together, they turn ambition into something workable.

A numerical goal accomplishes nothing.

Only the method is important, not the goal. By what method?

— W. Edwards Deming

A year-end planning meeting

Consider a professional services firm, meeting to set its plan for the upcoming year. The work is demanding, the clients are impatient, and the pace has been relentless. Maya, the managing partner, carries pressure from every direction—revenue expectations, client satisfaction, and the quiet responsibility of not burning out her best people.

Jordan runs operations. He sees the firm not as departments, but as a flow: leads turn into proposals, proposals turn into delivery, delivery shapes the client experience, and that experience determines renewals and referrals. In Deming’s terms, Jordan is paying attention to the system.

On the screen is a single slide: “GROWTH TARGET +25%.”

The instinct is immediate. Translate the number into activity. More marketing. More outbound. More urgency. More everything. That reflex is common—and risky.

Deming described this trap with a word that sounds theatrical but proves painfully accurate: internal goals without a method are “a burlesque.” In other words, planning turns into performance. People look busy. Pressure goes up. Very little actually improves.

The meeting shifts when Jordan asks a question most teams never slow down long enough to consider: Is twenty‑five percent within what our system can deliver—without breaking quality or burning people out?

That question doesn’t lower ambition. It rescues ambition from fantasy.

Turning the target into an aim

Rather than debating the number, Jordan changes the conversation. The team stops arguing about outcomes and starts clarifying purpose. Jordan sketches how revenue actually happens—from first contact to repeat work—and asks where the system could be changed deliberately. This is the essence of system leadership: improving capability instead of demanding better results from existing capability.

The growth slide is rewritten. They replace the solitary percentage with an aim statement that speaks to purpose rather than outcomes: “Improve the reliability of the client experience, while building a system of work our people can sustain.” This is not wordsmithing. It is design. An aim makes tradeoffs visible before the year begins. It tells people what “better” means. And it prevents revenue—important as it is—from becoming the thing people optimize at the expense of everything else.

A system must have an aim. Without an aim, there is no system.

— W. Edwards Deming

With the aim clear, the next step is practical. Jordan pulls up the last eighteen months of data—lead flow, close rate, delivery time, rework. Not to judge people. Not to explain every fluctuation. But to understand what the system currently makes likely.

Deming was blunt about this: “If you have a stable system, then there is no use to specify a goal. You will get whatever the system will deliver. A goal beyond the capability of the system will not be reached.” If the system is stable, effort alone will not change outcomes. Only changes to the system will.

A goal beyond the capability of the system will not be reached.

— W. Edwards Deming

That’s why Jordan’s conclusion lands so clearly: The system is doing exactly what it has been built to do. If the firm wants a different result, it needs a different method. Ambition doesn’t disappear—it simply moves from wishing harder to building a better system. The growth target becomes a forecast—a best prediction given current capability—and a signal of whether the system is improving.

Replacing pressure with learning

Many organizations respond to ambitious targets by launching a long list of initiatives. The result is predictable: diluted focus, shallow execution, and exhausted teams.

Maya and Jordan choose a different approach. They select two focused improvement efforts—two places where change could meaningfully increase capability.

The first effort sits in proposals. If scope clarity improves and response time shortens, the close rate should rise without needing more leads.

The second effort sits in delivery. If intake and handoffs improve, rework should drop—freeing capacity without longer hours.

They run each effort through a learning cycle—the team states a prediction, tests it with a small group, studies the results, and decides what to adopt, adapt, or abandon. This is not goal chasing. It is disciplined learning. And disciplined learning is how real aspiration becomes real progress.

Substitute leadership—and make it safe

None of this works unless people can tell the truth. Deming’s guidance here is unmistakable: “Eliminate management by objective. Eliminate management by numbers, numerical goals. Substitute leadership.” In practice, leadership means resourcing improvement, removing obstacles, and reducing fear.

Maya makes one commitment explicit: no one will be punished for bad news from the measures. That single decision changes the tone completely. Weekly reviews become sources of insight rather than judgment. People stop managing impressions and start improving the system. Over time, that becomes a real competitive advantage.

Most firms set targets and hope for heroics. A Deming‑style firm builds capability and learns calmly. It becomes steadier, clearer, and more trustworthy—both to clients and to its own people.

Eliminate management by objective.

Eliminate management by numbers, numerical goals.

Substitute leadership.

— W. Edwards Deming

Actionable Takeaways

You don’t need a perfect plan to start the year well. You need clarity and courage.

Write an aim in one breath. Include what you refuse to sacrifice.

Choose one or two improvement efforts that would meaningfully change the year. Improve where capability actually matters.

Establish a simple weekly pulse to see whether you’re getting better. A few signals you can trust.

Make it safe to surface problems. Bad news is information, not failure.

These steps turn planning from pressure into progress.

A better way to begin the year

End‑of‑year planning often feels like standing at the edge of a new year with a number in your hands, hoping it will be enough.

There is another way.

Carry the year on purpose. Start with an aim your people can recognize as true—how you want to serve, what you want to protect, and what you refuse to sacrifice. Then lead with method. Learn in the open. Improve deliberately.

When the aim is clear and learning is real, people don’t just comply. They commit.

And the year that follows doesn’t just look better on paper. It feels better to live through—steadier days, fewer knots in the stomach, and work that leaves people, and the organization, better off than they started.

You do not rise to the level of your goals.

You fall to the level of your systems.

— James Clear