On paper, the year looked exceptional. Demand was strong. The numbers were up and to the right. Everyone was happy. Inside the organization, the mood was confident, even relaxed. From the outside, it looked like success.

That is exactly the moment W. Edwards Deming warned leaders about.

He once observed, “It is easy to manage a business in an expanding market, and easy to suppose that economic conditions can only grow better and better.” His point was not that success is a problem, but that success can quietly disguise weakness.

It is easy to manage a business in an expanding market, and easy to suppose that economic conditions can only grow better and better.

— W. Edwards Deming

A very good year

To see what Deming meant, consider a nonprofit serving families through food assistance and job‑readiness programs. It had been a banner year. A new corporate partnership boosted funding. A positive media story brought in volunteers. Enrollment climbed. The board was pleased. Staff morale was high.

At a routine leadership meeting, the updates sounded exactly like you would expect in a good year.

Marcus, who oversaw operations, went first. “We’re serving more families than ever,” he said. “The handoffs are smoother, the wait is shorter, and volunteers are showing up.”

Elena, the executive director, added the development update. “Donors are leaning in,” she said. “We’re ahead of plan, and the support feels steady—for now.”

All of it was true. And yet Elena felt a quiet tension she couldn’t shake. It wasn’t fear. It wasn’t urgency. It was a question that didn’t quite fit the celebratory tone of the room: Are we improving… or are we just busy?

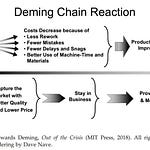

Deming would have recognized that moment instantly. When conditions are favorable, results can improve even if the underlying system stays weak. A strong economy, a generous donor cycle, or a surge of goodwill can lift outcomes without strengthening capability at all.

The tailwind trap

Strong results tell leaders what has happened. They do not explain why it happened, or whether it will happen again. In an expanding environment, ordinary management can look exceptional. Leaders can easily mistake momentum for capability and luck for skill. The danger is not celebrating success—it is assuming success proves the system is sound.

Deming warned that decline rarely announces itself. It arrives like dusk, so gradually that people don’t notice it happening. One day the numbers soften. Then variation increases. Then firefighting becomes normal. By the time leaders recognize the pattern, the room to maneuver has largely disappeared.

Elena sensed that risk, even though nothing appeared broken. Instead of asking for bigger goals or tighter targets, she asked a different kind of question. “If things got tighter next year,” she said, “if funding dipped or demand spiked, what would we wish we’d strengthened while we still had room to breathe?”

The room went quiet—not because the question was threatening, but because it was unfamiliar. Marcus answered first. “Cross-training,” he said after a pause. “Right now, a few people are holding too many threads.”

That one sentence revealed more about the system than any dashboard had. When performance depends heavily on a handful of individuals, results can look excellent right up until someone gets sick, leaves, or burns out. At that point, the organization discovers it has not built a system; it has built a reliance.

Elena heard it clearly. This wasn’t a staffing issue. It was a design issue.

From outcomes to capability

Deming taught that an organization doing well is in the best position—and has the greatest obligation—to improve. When survival pressure is low, leaders have something rare: the capacity to learn.

In a crisis, organizations default to urgency. Controls tighten. Pressure increases. Short‑term output becomes the priority. Sometimes that response is unavoidable. But Deming warned that improvement driven by pressure usually optimizes for speed, not learning, and leaves the system weaker in the long run. Good times create a different opportunity. They allow leaders to shift attention away from celebrating outcomes and toward strengthening capability.

A company that is doing well is in an excellent position to improve management, product, and service, and moreover has the greatest obligation to improve. A company that is on the rocks can only think of survival short-term.

— W. Edwards Deming

Up to this point, Elena and Marcus had been talking about results. The question now was how to see the system underneath those results. Elena wanted to know whether the organization understood what actually made the work hold together—and whether it could keep holding together when conditions shifted.

A small experiment

Rather than launching a major initiative, Elena proposed a modest experiment. For several weeks, the team would track a few measures of capability—not outcomes. They chose three: the time from first contact to receiving help, the rate of rework caused by missing or unclear information, and the time it took to onboard a new volunteer.

Marcus frowned slightly. “Those numbers are going to move around week to week.”

“Exactly,” Elena said. “If it’s normal noise, we won’t chase it. If there’s a real cause, we’ll go fix the cause.”

That distinction—between a normal wobble and a meaningful change—is central to Deming’s thinking. Most organizations do the opposite. A rough week triggers pressure. A complaint triggers correction of people. A delay triggers urgency. Deming warned that overreacting to everyday variation can make systems worse, not better.

Within weeks, patterns began to emerge. Delays clustered on Mondays. Rework spiked after a partner changed a form. Volunteer onboarding slowed dramatically whenever one staff member was out. None of this showed up in the headline numbers. Funding was still strong. Participation was still high. But the system was quietly revealing where it was brittle.

Instead of setting new targets, the team improved the system. They cross‑trained a role that had become a bottleneck. They standardized intake so rework didn’t depend on who answered the phone. They simplified onboarding so volunteers weren’t stranded when one person was unavailable. The changes were unremarkable on the surface, but their effect was profound. The work became more predictable. Learning accelerated. Capacity grew. The organization became less dependent on heroics and more resilient by design.

Why Deming matters most in good times

Deming once said that a healthy organization is in the best position to improve, and has the greatest obligation to do so. The nonprofit’s experience made that idea tangible: improvement was not driven by fear or crisis, but by foresight. This is why Deming matters most when things are going well. Good times provide the margin to learn, to see the system clearly, and to strengthen it before conditions change.

In any industry, organizations compete not just for customers or funding, but for resilience. They compete against complacency, against the belief that what worked this year will work next year, and against the slow drift of brittleness that success can conceal.

Actionable takeaways

If you want to use good times wisely, start small and keep it practical. Here are five moves that translate Deming’s insight into day-to-day leadership.

Pick one or two capability measures. Choose measures that reveal how strong the system is (flow, rework, onboarding, lead time), not just outcomes.

Review enough data to see patterns. Look at performance over time so you can distinguish a normal week-to-week wobble from a meaningful change.

Ask the “tightened conditions” question regularly. What would you wish you had strengthened if funding dipped, demand spiked, or staffing changed?

Improve the system, not the slogans. Crosstrain bottlenecks, standardize handoffs, and simplify steps where the process is brittle.

Treat improvement as stewardship. Use favorable conditions not to relax, but to strengthen the system that carries the aim forward.

Taken together, these steps turn momentum into resilience—so you’re not relying on good conditions to keep getting good results.

A closing thought

Good times are a gift. They are also a test.

They test whether leaders can resist the comfort of applause and invest instead in capability. They test whether organizations can strengthen their systems when they do not have to, so they can endure when they must.

Deming’s message is not to be afraid. It is to be wise.

If things are going well today, you have something precious: room to learn.

Use it.

It is easy to date an earthquake, but not a decline.

— W. Edwards Deming