Most leaders feel pressure in the same places. Costs creep up. Capacity feels tight. Customers wait longer than they should. Staff are busy, sometimes exhausted, and still the results don’t seem to move. The natural response is familiar. Push productivity. Raise targets. Add oversight. Ask people to move faster. It feels responsible. It looks like leadership.

And yet, very often, it quietly makes things worse.

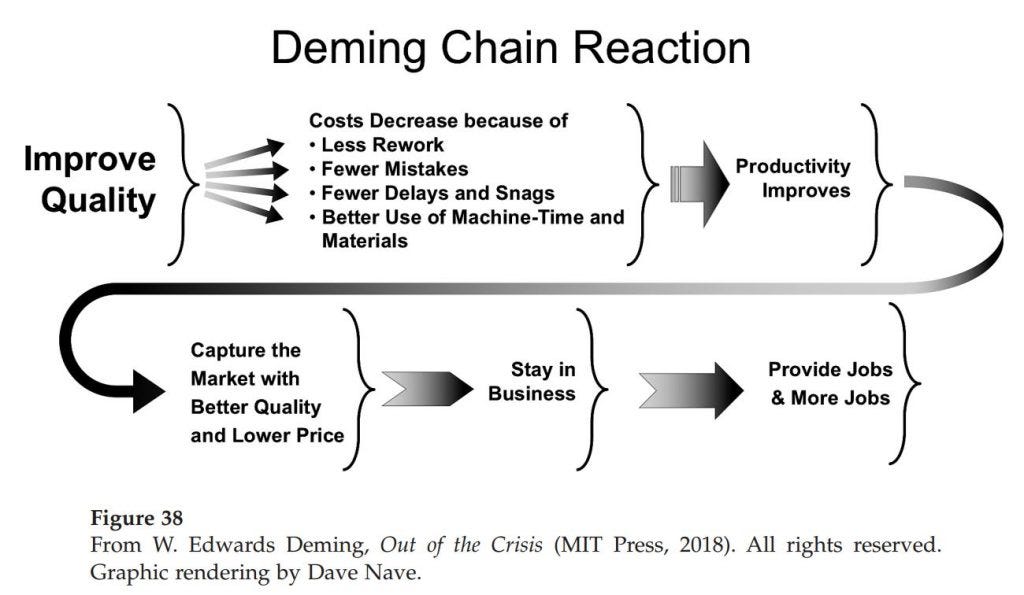

W. Edwards Deming offered a different way to think about improvement—one that runs counter to that instinct. In Out of the Crisis, he described what he called the chain reaction: a cause‑and‑effect sequence that begins not with cost or productivity, but with quality. Deming was clear that this was not a motivational idea. It was an explanation of how systems actually improve.

If you improve quality, Deming said, “The result is a chain reaction—lower costs, better competitive position, happier people on the job, jobs, and more jobs.” Each outcome depends on the one before it. Miss the starting point, and the rest of the chain never really takes hold.

The result [of improving quality] is a chain reaction—lower costs, better competitive position, happier people on the job, jobs, and more jobs.

— W. Edwards Deming

The logic behind the chain

At first glance, Deming’s chain reaction looks almost too simple: improve quality, and good things follow. But Deming was not offering encouragement or aspiration. He was offering a way of thinking that depends on sequence. The chain reaction works only when its links unfold in the right order.

It starts with quality. When quality improves, costs come down—not because someone demanded savings, but because waste leaves the system. Deming described the mechanism plainly: “Improvement of quality transfers waste of man‑hours and of machine‑time into the manufacture of good product and better service.” In practice, this shows up as less rework, fewer mistakes, and fewer delays and snags. Time that was once spent fixing problems is freed to do useful work.

Improvement of quality transfers waste of man‑hours and of machine‑time into the manufacture of good product and better service.

— W. Edwards Deming

As that waste leaves, capacity returns. Only then does productivity improve—not because people are working harder, but because the system is able to work as intended. Over time, better quality and lower total cost translate into better value. Trust strengthens. Performance stabilizes. The organization can stay viable—or, in mission‑driven settings, continue to serve. Jobs become easier to protect, and growth becomes possible.

The meaning of quality

In many organizations, the word quality is narrowed to outputs, results, or compliance measures. Deming’s meaning was broader and explicitly managerial. He tied quality to meeting the needs of the customer, present and future, and placed responsibility squarely with leadership. Quality, in Deming’s sense, is not about effort. It is about how the work itself is designed.

Operationally, quality shows up as reliability. The work arrives ready. Prerequisites are clear and present. Information is complete. Handoffs do not require rescue. The process is capable of producing a good result without looping back on itself. When those conditions are not met, the system creates rework—and that rework is where cost and capacity quietly disappear.

Watching the chain reaction at work

Riverview Health System’s specialty clinic had an eight-week wait for new appointments. Pressure was mounting. Access needed to improve, but headcount was frozen. Maria, the clinic operations director, saw the same pattern week after week. The clinic was full. The staff were busy. And the backlog wasn’t moving.

“Everyone is working flat out,” she said during a Monday review. “But the waiting list isn’t changing.”

Instead of asking people to work harder, Maria asked a different question: where is the system creating rework? She and the medical director agreed to look more closely.

“Let’s stop guessing,” he said. “Let’s count how often work comes back.”

For two days, the team tracked repeat work. They categorized callbacks, delays, and corrections tied to referral defects, missing prerequisites, authorization issues, unclear orders, and documentation rework. When they reviewed the results, the answer was unmistakable.

“Nearly a third of our calls aren’t new demand,” Maria said quietly. “They’re cleanup.”

That made the starting point clear. Quality had to be addressed at the entry point. They focused on new rheumatology referrals. The core problem wasn’t clinical judgment. It was incomplete information. Intake staff chased labs. Nurses re-triaged. Visits ran late because prerequisites were missing.

“If we fixed this upstream,” the medical director observed, “the whole day would change.”

The team redesigned the referral process. Required fields were clarified. Prerequisites were explicit. If something was missing, the visit wasn’t scheduled; a clear request went back immediately. Within weeks, the day felt different.

“The phones are quieter,” one scheduler noted. “We’re not constantly fixing things.”

Phone calls dropped. Reschedules declined. Visits started on time more often. Costs fell because rework fell. As correction work faded, capacity returned. With the same staffing level, the clinic completed more work that stayed complete. Access improved. The waiting list began to shrink. Productivity improved—not because people were pushed harder, but because failure demand no longer consumed capacity. Over time, reliability strengthened trust with referring practices and patients. Performance stabilized. Leaders could plan instead of firefighting. Jobs were protected not through cuts, but through predictability.

The improvement didn’t come from working harder or managing tighter. It came from choosing the right starting point—and then letting the rest of the chain do its work. Once quality was addressed upstream, the system began to change on its own. Rework fell, capacity returned, and productivity followed without being forced. What looked at first like a stubborn access problem turned out to be a design problem, and fixing that design made improvement both durable and calm.

Putting the chain reaction to work

Under pressure, it’s tempting to start the chain in the middle. Lower costs become mandates. Productivity becomes a target. But cost and productivity are outcomes of a system. When leaders pressure outcomes without improving the system that produces them, rework grows, delays lengthen, and capacity shrinks. This is why Deming insisted on quality as the starting point. Without it, the later links have nothing solid to stand on.

The chain reaction becomes practical when leaders shift where they put their attention. Rework is a good place to begin. Treated as noise, it’s frustrating. Treated as data, it’s revealing. Rework shows where the system isn’t capable and where quality is breaking down upstream. That perspective reshapes how quality is defined. Instead of abstract goals, quality becomes observable. What does “ready” actually mean at the entry point? What conditions must be present so work flows forward instead of circling back?

With those questions in view, improvement naturally moves upstream. Ambiguity is reduced. Prerequisites stabilize. Handoffs become clearer. Downstream teams no longer have to compensate for what the system failed to provide. Progress then appears in a predictable order. Callbacks decline. Reschedules ease. Overtime falls. These are early signs that cost is coming down because rework is leaving the system. As capacity returns, productivity follows.

Seen this way, the chain reaction isn’t a technique. It’s a discipline of starting points. As Deming warned, “A bad system will beat a good person every time.”

A bad system will beat a good person every time.

— W. Edwards Deming

Actionable takeaways

These are not tactics to apply all at once. They are starting points—ways to begin aligning daily management decisions with the logic of the chain reaction.

Measure rework, not effort. For a short window—one or two days—track how often work loops back: clarifications, missing inputs, avoidable exceptions, reschedules, callbacks, and other “cleanup.” Treat the count as a map of where the system is failing, not a scorecard on people.

Define “quality” as entry-point reliability. Make “ready” explicit: required information, prerequisites, and clear handoffs. Build these conditions into the process (templates, required fields, checklists, upstream agreements) so downstream teams don’t have to rescue the work.

Follow the chain in order. Look first for fewer snags—less rework, fewer interruptions, fewer delays. Then watch capacity return. Only after that should you expect productivity and results to improve. Resist the temptation to start in the middle.

Taken together, these actions help leaders stay anchored to the first link. They keep attention where improvement actually begins, even when pressure pushes hard in the opposite direction.

Start the chain reaction

Deming’s chain reaction isn’t about doing more. It’s about starting in the right place. When leaders improve quality, they remove the causes of rework and delay that quietly drain their systems. Capacity returns. Productivity improves as a consequence, not a demand. Stability becomes possible. Once this way of thinking takes hold, it’s hard to unsee. Cost and productivity stop looking like levers to pull and start looking like outcomes to be earned.

If improvement is the aim, hold the line on the first link. Quality first.