When a company struggles with motivation, most leaders reach for incentives — bonuses, competitions, maybe a few gold stars. It’s instinctive. If people aren’t performing, we assume they just need more motivation. But what if the very tools we use to “motivate” people are quietly destroying their motivation?

W. Edwards Deming thought deeply about this question. In his System of Profound Knowledge, one of the four interrelated components is psychology — understanding human behavior, what drives people, and what stifles them. He believed that management must understand psychology not to manipulate people, but to work with human nature instead of against it.

Let’s bring this to life through a story.

A misguided incentive

Sarah manages a small team of eight. She’s sharp, caring, and determined to help her team succeed. But lately, sales have flattened, customer complaints are rising, and morale has taken a hit. People seem to be coasting. So, Sarah decides to inject some energy into the team.

“Starting this quarter,” she announces, “we’re rolling out a new incentive program. Top performer each month gets a $500 bonus. Let’s make it fun — a little friendly competition!”

Across the table, Alex, one of her most reliable employees, shifts in his chair. He frowns slightly before asking, “So… if I help Sam with his project, that means I’m lowering my score, right?”

And there it is — the quiet sound of trust leaving the room.

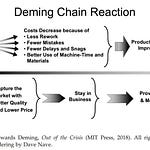

Deming warned us about this. He once said, “The greatest waste in America is failure to use the abilities of people.” And one of the fastest ways to waste human potential is to create systems that pit people against one another instead of aligning them toward a shared aim.

The greatest waste in America is failure to use the abilities of people. — W. Edwards Deming

The psychology of intrinsic motivation

Deming believed people are born with intrinsic motivation — a natural desire to learn, contribute, and take pride in their work. Children, for example, are naturally curious and eager to improve. They don’t need to be bribed to explore. But in many workplaces, management replaces that inner drive with a maze of extrinsic motivators: contests, rankings, bonuses, and “Employee of the Month” plaques.

These incentives may create bursts of short-term performance, but they do long-term damage. They teach people to chase rewards instead of mastery. They shift focus from the joy of good work to the fear of losing. They undermine teamwork, creativity, and — ironically — quality.

Deming’s insight was that when management uses rewards and punishments as levers, it signals something deeper: “We don’t trust your internal drive.” And that message quietly corrodes pride and engagement.

From manipulation to support

Back in our story, Sarah begins noticing side effects. Alex stops volunteering ideas. Sam rushes through his tasks, cutting corners to stay ahead in the leaderboard. Collaboration fades. She’s unintentionally turned teammates into competitors.

Frustrated, Sarah meets with her mentor, who offers a different lens: “Instead of trying to motivate your people, try to understand what’s demotivating them. Remove the barriers that keep them from doing good work.”

So, Sarah cancels the contest and calls a new meeting. “I realized we’ve been competing instead of collaborating,” she admits. “I want to know what’s getting in your way — what makes it hard to do your best work?”

Alex speaks up first. “Honestly? The reporting software is so slow, it eats up hours every week. We’re wasting time we could be spending helping customers.”

That’s real psychology in action — uncovering frustration instead of disguising it with prizes.

Sarah takes action. She works with IT to fix the reporting system, streamlining workflows. She also invites the team to design their own quality checks. Within a few months, customer complaints drop. Sales improve. But what stands out most isn’t the numbers — it’s the energy. People care again.

Deming’s lesson: Help people do a better job

Deming put it simply: “The aim of leadership should be to improve the performance of man and machine, to improve quality, to increase output, and simultaneously to bring pride of workmanship to people.” The manager’s role is not to motivate through fear or rewards, but to create conditions for pride in workmanship. That means removing obstacles, clarifying purpose, and showing respect for the human need to grow and contribute. Psychology, in Deming’s view, isn’t a soft skill — it’s a management science. It’s the art of building systems that align with human nature, not fight it. When you do that, you don’t have to push people to perform. You simply stop holding them back.

The aim of leadership should be to improve the performance of man and machine, to improve quality, to increase output, and simultaneously to bring pride of workmanship to people. — W. Edwards Deming

Actionable takeaways

Stop trying to “motivate” people. Assume your employees are already motivated — your job is to avoid killing that motivation.

Remove barriers to pride in workmanship. Ask, “What frustrates you about doing good work?” Then fix it.

Replace competition with collaboration. Design systems where everyone wins when the customer wins.

Honor intrinsic motivation. Recognize effort, learning, and contribution — not just outcomes.

Lead with respect for human nature. As Deming taught, “People are different. They are born with different abilities, and management must be aware of these differences.” Treat variation in people as a strength to be understood, not a flaw to be corrected.

Understanding psychology, as Deming defined it, is not about managing emotions. It’s about understanding the system of human motivation — and building organizations where people can take pride in their work. When you do that, quality, innovation, and joy naturally follow. Because in the end, the real competitive advantage isn’t control — it’s trust.