Most leaders have lived some version of this: you coach a team, send follow-up emails, give a firm talk about accountability—but a few weeks later, the same problems are back. It’s easy to conclude that the issue is motivation or discipline. If people would just try harder, surely results would improve, right?

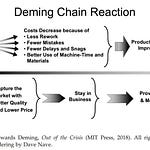

W. Edwards Deming suggested something very different. He argued that most performance comes not from the effort of individuals, but from the system they work in—the processes, policies, tools, measures, and handoffs that shape their day. In his words, “Everyone doing his best is not the answer.” The central leadership question is not, How do I get people to do their best? but rather, Have we designed a system in which their best is even possible?

This distinction between leading people and leading a system feels abstract until you see it play out in real work. The story of Maria and Jamal makes it concrete.

When “Be more careful” isn’t enough

Maria is the chief nursing officer at a busy regional hospital. On paper, the organization looks respectable. In practice, a pattern of small failures is beginning to add up.

Medication errors at discharge are creeping upward. Patients complain that instructions are confusing. Nurses stay late to clean up documentation. Readmission penalties are cutting into already thin margins. Turnover among experienced nurses is quietly rising as people burn out.

Maria does what many conscientious leaders do. She asks her team to slow down and be more careful. The hospital offers refresher training on medication safety. Posters appear in hallways reminding staff to double-check prescriptions.

For a few weeks, the numbers improve. Then, inevitably, problems return.

Maria finds herself repeating the same phrases: “We’ve covered this before.” “We just talked about this in the staff meeting.” “Why is this still happening?”

From a traditional leadership lens, the answer seems obvious: people are not paying attention. The solution is to lead the people harder—more reminders, sharper consequences, stronger language about accountability.

Jamal, a quality improvement specialist, suggests a different starting point. “What if we stop asking, ‘Who messed up?’” he says in a meeting, “and start asking, ‘Why is it so easy to make this mistake here?’”

That question quietly moves the focus from the people to the system.

Seeing the system instead of the individual

Jamal proposes that they study one recurring problem: medication errors at discharge. Rather than issuing another memo, they invite a small cross-functional group into a conference room—nurses, a hospitalist, someone from pharmacy, and an IT analyst. Together, they walk through an actual discharge step by step.

On the whiteboard, the discharge process quickly sprawls into a maze. There are seventeen separate steps. Three software systems do not share data cleanly, so staff copy and paste information between screens. Pharmacy hours do not align with the hospital’s peak discharge times, forcing last-minute workarounds. Two performance metrics quietly pull in opposite directions: nurses are praised for moving patients out quickly to make beds available, while physicians are scolded if documentation is anything less than perfect.

In this light, the recurring errors look less like carelessness and more like the predictable output of a tangled system. Maria voices the realization that has been forming in her mind. “So every day we’re telling people, ‘Go faster and be flawless,’ inside a process that practically guarantees rework.”

The workers are handicapped by the system, and the system belongs to management.

— W. Edwards Deming

Deming’s point lands with new clarity. The nurses are not the system. They are working inside the system. As long as that system remains unchanged, no amount of exhortation will deliver reliable improvement.

Changing the work, not the willpower

Instead of launching a grand initiative, the group starts with small, deliberate experiments—PDSA cycles (Plan–Do–Study–Act). Each cycle is designed to change the work itself, not to add more reminders.

First, they standardize the discharge checklist so that nurses, physicians, and pharmacy all use the same list in the same order. This simple change reduces variation in how discharges are prepared.

Next, they adjust scheduling to ensure that a pharmacist is explicitly available for discharge consults during the busiest hours, rather than assuming someone will “fit it in.”

IT builds a single medication summary view so staff no longer have to copy and paste between systems. Information that previously lived in three places now appears on one screen.

At each step, Jamal keeps returning to the same principle: “Let’s not ask people to remember one more thing,” he says. “Let’s change the work so the right thing is the easy thing.”

Over the next few weeks, the tone of incident reviews begins to change. Nurses bring forward near-misses caught by the new checklist. Physicians note that final medication lists are clearer. There are still exceptions, but the patterns are different.

“You know what’s strange?” Maria says during a review. “We’re not seeing ‘careless nurse’ anymore. We’re seeing ‘the new checklist caught an issue before discharge.’”

They have not changed the people. They have changed the system those people work in. Medication errors decline. Readmissions begin to fall. Patient satisfaction nudges upward. Turnover among experienced nurses slows.

Deming summarized this shift succinctly: “The job of management is not supervision, but leadership.” In this context, leadership means taking responsibility for the system, not searching for better slogans to give to already overworked staff.

Leading the system is a competitive advantage

Maria’s hospital does not suddenly become perfect. But it becomes different from many of its peers in one crucial way: it has begun to treat recurring problems as clues about the system rather than as evidence of individual failure.

While other organizations double down on performance reviews, stricter policies, and motivational campaigns, Maria and Jamal invest their energy in redesigning how the work works. They reduce unnecessary variation. They remove non–value-adding steps. They align measures so that people are not pulled in contradictory directions.

Deming estimated that roughly 94% of results come from the system, not from individuals—making improvement chiefly a management responsibility.

This orientation becomes a quiet competitive advantage. Results improve, yes—but something deeper shifts as well. People feel safer raising problems. Frontline staff see that leadership is willing to change processes, not just tighten expectations. Improvement becomes part of the daily conversation instead of an occasional project.

The same pattern applies far beyond healthcare. In software, manufacturing, education, professional services, and nonprofits, leaders face the same choice: spend another year trying to “fix” people, or learn to lead the system they work in.

Actionable takeaways for leaders

If you want to move from leading people to leading a system, you do not need a massive reorganization. You can start small, the way Maria and Jamal did.

1. Treat recurring problems as system signals. When the same issue appears across shifts, locations, or teams, assume it is designed into the work. Ask, “What about our process makes this outcome likely?” before you ask, “Who is at fault?”

2. Go and see the actual flow of work. Dashboards and reports are not enough. Spend time where the work happens. Watch a process from start to finish with the people who live inside it. Have them talk you through every step.

3. Involve the people who do the work in redesigning it. Maria’s breakthrough came not from a closed-door meeting, but from a cross-functional group mapping the discharge process together. The people who touch the work every day are best positioned to see where it fights them.

4. Change the environment, not just the message. Instead of crafting stronger speeches, look for ways to remove steps, combine screens, standardize checklists, or align schedules. Aim to make the desired behavior the path of least resistance.

5. Align measures so they do not conflict. If one metric rewards speed and another punishes any error, you create impossible tradeoffs. Review your key metrics and ask whether they pull people in the same direction.

6. Think in cycles, not one-time fixes. Use PDSA or similar cycles to run small experiments. Learn from each change and build on what works. System leadership is an ongoing practice, not a single project.

A different way to lead

In the end, most people do not come to work hoping to fail. They want to go home feeling that their work mattered and that it was possible to do it well. When leaders focus only on motivation and discipline, they overlook the daily friction that makes good performance fragile.

Leading a system means taking responsibility for that friction. It means asking uncomfortable questions about how the organization itself produces variation, delay, confusion, or waste. It means being willing to redesign the work—not just redirect the people.

The payoff is more than better numbers on a report. When you lead the system, you offer your people a fair chance to succeed. You create conditions where ordinary individuals can achieve consistently good results on an ordinary day. And you give your organization something rare in today’s world of work: the ability to improve, on purpose, again and again.

The job of management is not supervision, but leadership.

— W. Edwards Deming