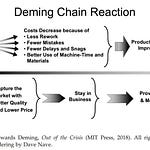

How many people in your organization could clearly explain why their work matters—how what they do connects to the larger purpose of the business? If the answer is “not many,” you’re in good company. Most employees see their part of the process but not how it fits into the whole. They may know what their job is, but not why it exists. Dr. W. Edwards Deming believed this was one of the great failings of modern management. He wrote that “a system must have an aim. Without an aim, there is no system.” And the responsibility for understanding and communicating that aim falls squarely on the manager.

When a manager helps people understand how their work contributes to the system’s aim, something profound happens. Confusion turns into clarity. Competition between departments gives way to cooperation. Instead of optimizing their own metrics, people begin improving the whole. This is not management as control; it’s management as education. And it begins with explaining the meaning of a system.

A manager understands and conveys to his people the meaning of a system. He explains the aims of the system. He teaches his people to understand how the work of the group supports these aims. — W. Edwards Deming

A story from the floor

Let’s imagine a mid-sized manufacturer of specialty packaging—nothing glamorous, but a steady business with loyal customers. Karen is the operations manager. Luis runs one of the die-cutting machines on the production floor. One morning, Luis approaches Karen with frustration written all over his face.

“Karen, I keep getting told to cut faster,” he says, “but then quality sends half my sheets back. If I slow down, I get scolded for falling behind. Which one do you want?”

Karen sighs. She’s heard this before—from Luis, from others. The plant’s metrics emphasize speed, but rework and late shipments are rising. The problem isn’t Luis—it’s the system.

“Let’s talk about that,” Karen replies.

Later that morning, she gathers her team around a whiteboard. In three boxes, she writes Sales → Production → Customer.

“Our system isn’t about ‘more output,’” she begins. “It’s about on-time delivery of defect-free packaging that delights the customer. Every part of our process exists for that purpose.” She explains how cutting speed affects quality, how rework delays shipping, and how delays disappoint customers and strain sales. The group begins to see that “production” isn’t a standalone department—it’s part of an interdependent system.

Luis nods slowly. “So,” he says, “it’s not about cutting faster. It’s about helping the next step succeed.”

Karen smiles. “Exactly. You’re part of a system that depends on you.”

What Deming meant by “Understanding the system”

Deming described a system as “a network of interdependent components that work together to try to accomplish the aim of the system.” The word interdependent matters here. Each part relies on the others. When one part improves at the expense of another, the system as a whole suffers.

That’s why managers must resist the temptation to push local optimization—like demanding faster output from Luis—without considering the broader effects. It might make a chart look better in one department, but it often creates waste, frustration, and loss elsewhere.

Deming warned against this kind of “sub-optimization,” noting that “every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets.” If your system produces conflict, rework, or burnout, that’s not a failure of your people—it’s a reflection of how the system is managed.

Karen’s shift in focus—from individual targets to system aims—transformed how her team worked together. She didn’t just issue new orders; she provided understanding.

From supervision to leadership

A manager who explains the meaning of a system becomes more than a supervisor of tasks—they become a teacher of purpose. Deming wrote in The New Economics, “The job of management is not supervision, but leadership.” Leadership, in his sense, is about helping people see the system, learn from it, and contribute to its continual improvement.

The job of management is not supervision, but leadership. — W. Edwards Deming

Karen’s story may be fictional, but the lesson is very real. In every business—manufacturing, software, healthcare, education—the same principle applies. People cannot improve what they do not understand.

When you teach your team how their work supports the system’s aim, you align energy and creativity toward a shared purpose. You replace blame with curiosity. You move from firefighting to improvement.

And that understanding, Deming would say, is a competitive advantage.

Actionable Takeaways

If you’re a manager or business owner, here are four practical steps you can take this week to put Deming’s principle into action:

Clarify the aim of your system.

Write one clear sentence: What is our organization for? Every process, policy, and decision should connect to that aim.Make the interdependencies visible.

Draw your workflow on a whiteboard. Show how each part affects the others. Discuss the handoffs, not just the silos.Teach through examples.

Identify one situation where local optimization hurt the whole system. Use it as a learning moment.Reinforce purpose constantly.

In meetings, reviews, and planning sessions, ask: “How does this serve the aim of our system?” Keep that question alive.

Managers who help people understand the system don’t just improve performance—they build trust, pride, and shared responsibility. As Deming reminded us, “The transformation is everyone’s job.” But it begins with leaders who are willing to teach the meaning of the system.

The transformation is everybody’s job. — W. Edwards Deming