Every day, leaders make decisions — sometimes by the numbers, sometimes by gut feel. But what if those numbers don’t mean what we think they do? In the world of management, few concepts are as powerful or as misunderstood as variation. Dr. W. Edwards Deming, the father of modern quality and systems thinking, believed that our ability to understand variation — to truly see the difference between signal and noise — determines whether we manage with wisdom or with chaos.

A spike in defects

Meet Sarah, the operations manager of a small manufacturing company that produces precision components for electric motors. Every morning, she checks a dashboard showing yield rates, defect counts, and output per hour. Her team is competent, disciplined, and proud of their work.

One morning, Sarah notices that the defect rate has jumped from 1.8% to 2.9%. Frowning, she calls in Tom, one of her most experienced line supervisors. “Tom,” she says, “this is the second time this month the defect rate has gone up. What’s going on down there?”

Tom shifts uncomfortably. “We’ve been doing everything the same,” he says. “Same people, same materials. Honestly, it just feels like normal ups and downs.”

Normal ups and downs. Sarah doesn’t realize it yet, but that phrase holds the key to the entire situation.

Common causes vs. special causes

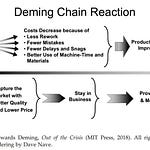

Dr. Deming taught that all processes — in business, in production, even in life — show variation. No two days, no two products, no two employees perform identically. Some variation is built into the system; other variation comes from something unusual. Deming called these common causes and special causes.

Common causes are the natural, predictable fluctuations in a stable process — the everyday randomness of reality.

Special causes are signals — events or factors outside the system that create unusual variation.

When managers fail to distinguish between the two, they make destructive decisions. As Deming warned, “A manager who does not understand variation is doomed to react to every change as if it were a special cause.”

A manager who does not understand variation is doomed to react to every change as if it were a special cause. — W. Edwards Deming

Mistaking noise for signal

Sarah assumes that something special caused the spike in defects. Her instinct is to act — to tighten inspections, retrain staff, or revise procedures. But what if Tom is right? What if this is just noise — part of the natural rhythm of a stable system?

If Sarah were to plot her daily defect rates over time — a simple run chart, or better yet, a control chart — she might see that her process consistently varies between 1.5% and 3.2%. In that case, 2.9% isn’t a problem. It’s just where the data happens to fall today.

When managers react to every wiggle in the numbers, they introduce instability. They adjust, reassign, and “fix” things that aren’t broken. Deming called this tampering — changing a stable system based on random fluctuation. Over time, tampering increases variation, lowers morale, and degrades performance.

Tom feels this firsthand. “We make adjustments every time she sees a change,” he tells a colleague, “And the next day it swings the other way. We can’t win.” He’s right. When leaders mistake noise for signal, they punish people for patterns the system itself creates. The result is frustration, fear, and a loss of faith in management.

Seeing the system

Dr. Deming often said, “If you can’t describe what you are doing as a process, you don’t know what you’re doing.” Understanding variation is part of that knowledge. It’s not just a statistical exercise — it’s a lens for seeing how work really happens.

If you can’t describe what you are doing as a process, you don’t know what you’re doing. — W. Edwards Deming

Here’s what Sarah could do differently, and what any leader can apply immediately:

Plot data over time.

Don’t rely on single numbers or isolated reports. Patterns tell stories that point data never can.Ask if the process is stable.

If variation is random and predictable, focus on improving the system itself — better methods, clearer processes, smarter design — not blaming individuals.Only act when there’s evidence of a special cause.

A point outside the control limits, or a non-random pattern, signals something new. Investigate then — not before.

Deming put it simply: “Management of a system requires knowledge of the interrelationships between the components of the system and of the variation within it.” In other words, leadership begins with understanding what can be predicted, and what cannot.

Management of a system requires knowledge of the interrelationships between the components of the system and of the variation within it. — W. Edwards Deming

Leading with knowledge, not reaction

When leaders grasp variation, they move from firefighting to stewardship. They stop chasing yesterday’s numbers and start designing systems that improve tomorrow’s outcomes. They ask better questions, make fewer mistakes, and earn the trust of the people who do the work.

The next time your numbers fluctuate — a sales dip, a customer complaint, a change in productivity — take a breath. Ask yourself: Is this a signal, or just noise? Because reacting to noise doesn’t improve the process. It only adds confusion.

Understanding variation isn’t just for statisticians. It’s a management skill — and perhaps the most important one of all. It’s how we move from managing by fear to managing by knowledge. And in Deming’s words, “Without data, you’re just another person with an opinion.” But without understanding variation, even data can lead you astray.

Without data, you’re just another person with an opinion. — W. Edwards Deming

Apply this in your organization

If you want to start applying Deming’s lesson on variation in your own organization, try this:

Pick one key metric you review regularly — quality rate, revenue, customer satisfaction, anything.

Graph it over time. Don’t look at daily or weekly snapshots; look at the flow.

Look for stability. Are you seeing predictable fluctuations, or true signals of change?

Resist the urge to react to every up and down. If the process is stable, focus on improving the system, not the people.

This week, aim to be more like Tom — patient enough to see the pattern — and less like Sarah before she learned the lesson. In Deming’s philosophy, understanding variation isn’t about statistics. It’s about respect for reality.