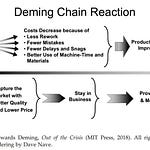

Most business leaders believe performance problems come from people. Someone didn’t care enough, didn’t try hard enough, or just “messed up.” But W. Edwards Deming — one of the most influential thinkers in management history — taught something radically different. He said, “A bad system will beat a good person every time.” In other words, even your most talented people can’t succeed if the system they work in is designed to fail. And most of the time, that’s exactly what’s happening.

A bad system will beat a good person every time. — W. Edwards Deming

This lesson, part of Deming’s System of Profound Knowledge, is called Appreciation for a System. It’s about understanding that every organization is a network of interdependent parts — departments, teams, and processes — working toward a shared purpose.

And crucially, Deming reminded us that every system must have an aim — a clear, meaningful purpose that benefits everyone touched by the organization: customers, employees, suppliers, and society. Without a shared aim, even good people and good processes will pull in different directions.

Let’s bring this idea to life through a familiar story.

A familiar problem

Meet Sarah, a manager at a mid-sized manufacturing company that makes precision parts for electric bicycles. For months, she’s been frustrated. Production numbers are down. Customer complaints are up.

One afternoon, she pulls Jason, one of her best machinists, into her office. “Jason, we’ve got to pick up the pace,” she says. “The board’s on my back about these delays. Can you stay late and help hit the quota?”

Jason hesitates. “I can,” he says, “but honestly, half my time is spent fixing the measurements from the CAD files. Engineering keeps changing specs after we start cutting. We never know which version’s the right one.”

Sound familiar? Sarah thinks she has a worker problem. But Jason is describing a system problem. The real issue isn’t in his effort — it’s in how the parts of the organization interact.

Understanding the system

Deming’s idea of Appreciation for a System is simple, but profound. Every organization is made up of interdependent parts — each performing a function, but none existing in isolation. If you improve one part without considering its connection to others, you risk making the whole worse. When Sarah pressures Jason without understanding the upstream design process, she creates short-term motion but long-term waste.

To truly see the system, leaders must ask:

How do our processes connect?

Where do handoffs create friction?

Who depends on whom — and for what?

And what’s the aim we’re all working toward?

Deming taught that the job of management is to optimize the system as a whole, not to judge or reward individual parts in isolation. When leaders act as if each department is an island, they unknowingly create competition where cooperation should exist. As Deming put it, “The aim of leadership should be to improve the performance of man and machine, to improve quality, to increase output, and simultaneously to bring pride of workmanship to people.”

The aim of leadership should be to improve the performance of man and machine, to improve quality, to increase output, and simultaneously to bring pride of workmanship to people. — W. Edwards Deming

A shift in thinking

A week later, Sarah decides to do something she’s never done before: map the entire workflow. She invites people from engineering, production, and quality control into the same room. “I realize I’ve been asking each of you to go faster,” she admits, “but I never stopped to ask how your work connects. Let’s map it together.”

As the group starts drawing out their process, a pattern emerges. Engineering updates CAD files after production begins — and those updates don’t automatically reach the shop floor. The result? Jason and his team cut parts from outdated specs.

Jason leans forward. “So, if we just sync file versions daily, we’d stop cutting the wrong parts?”

The lead engineer nods. “Exactly. We can automate that alert in the system.”

Then Sarah asks one more question. “What’s the aim of all this work? Why are we here?”

After some discussion, the team agrees that their purpose isn’t just to ship parts faster — it’s to build components that make electric bicycles safer, more reliable, and more enjoyable for riders — in a way that supports customers, respects employees, and sustains the business. That aim reframes everything. It’s not just about speed or quotas. It’s about delivering value to everyone touched by their work.

Within weeks, productivity improves — not because people worked harder, but because they finally worked together, guided by a shared aim.

Lessons for leaders

Sarah’s story illustrates a truth most leaders eventually learn the hard way: you can’t manage outcomes if you don’t manage the system that produces them.

Here are four takeaways you can apply right now.

See your organization as a system. Draw the flow of work from customer request to delivery. Where are the loops, the delays, the rework? Visualize it — because you can’t improve what you can’t see.

Look between departments, not just within them. Deming reminded us that most problems occur “at the interfaces” — the handoffs no one owns. Pay attention to those boundaries.

Shift blame from people to process. When something goes wrong, resist the reflex to ask, “Who messed up?” Instead, ask, “What in our system made this the likely outcome?”

Give the system a meaningful aim. Make sure everyone knows the ultimate purpose of their work — one that serves customers, employees, suppliers, and society. Profit follows, but it isn’t the aim.

Deming believed leadership is about designing the conditions for success. Your job isn’t to motivate people to do better work inside a broken system; it’s to create a better system so they can do their best work naturally.

Closing thoughts

In Sarah’s case, the breakthrough didn’t come from heroics. It came from humility — the willingness to see her team as part of a living, interdependent system. Once she did, improvement followed naturally.

Your organization — whether it builds bicycles, software, or sandwiches — is also a system. The question is: do you see it that way? Because once you do, everything changes. You stop managing by firefighting and start managing by design. You stop blaming individuals and start improving interactions. And you begin to understand what Deming really meant when he said, “It is not enough to do your best; you must know what to do, and then do your best.”

It is not enough to do your best; you must know what to do, and then do your best. — W. Edwards Deming

Leadership isn’t about driving people harder — it’s about shaping the system they work in. When you see your organization as a system, you stop chasing symptoms and start solving causes. That’s how sustainable improvement begins. So, take a page from Deming — and from Sarah. Step back. Look across the whole. Because once you see the system, you’ll never see your business the same way again.