Deming principles in action: How Walgreens increased inclusivity through systems thinking

The story of how, in 2003, Walgreens committed to make its distribution centers more inclusive to people with disabilities

The most valuable "currency" of any organization is the initiative and creativity of its members. Every leader has the solemn moral responsibility to develop these to the maximum in all his people. This is the leader's highest priority.

— W. Edwards Deming

In the Fall of 2003, Randy Lewis, one of Walgreens’s Senior Vice Presidents, presented a proposal to the Walgreens Board of Directors to build a state-of-the-art distribution center (DC) in Anderson, South Carolina. He told board members that the DC would be the most expensive facility in the company's history and incorporate the latest technological advances. Furthermore, he promised, the ROI would be higher than similar DCs, and that a minimum of 10% of the workforce would be people with disabilities, working side-by-side with other employees, held to the same work standards, and paid at the same rate. [1]

Working in a DC is physical, demanding work, requiring perfect coordination between the people in the DC and sophisticated, sometimes dangerous, machinery amid an army of moving forklifts, hand trucks, and bicycle messengers. Each day, hundreds of crates packed with thousands of unique products arrive on the inbound docks of each Walgreens distribution center. Employees unpack each crate, separate, and repack their contents into small batches distinct to each store, then deliver these new shipments to more than 9,000 retail pharmacies across the United States. Speed, accuracy, and safety are paramount; any failure means a lost sale and, possibly, a lost customer.

Before the new DC, daily pressures to meet operational goals at Walgreens typically created a process-focused culture that traditionally sacrificed the needs of people in favor of maintaining production metrics. According to a study of Walgreens DC managers [2], management practices prior to construction were autocratic, process-oriented, and solely focused on metrics—managers had limited autonomy to change prescribed processes, and workers who failed to meet the standard quota were fired.

Tapping the potential of all people

Business visionary W. Edwards Deming believed that all employees have the potential to contribute to the success of an organization, and that management has a responsibility to create an environment that allows employees to do so. He argued that, when employees are given the support and resources they need to succeed, they are more likely to be motivated and engaged, and that will lead to higher levels of productivity and quality. [3]

Introduced to Deming's quality philosophy during graduate school in the early 1970s, Lewis's later experiences as a systems consultant confirmed Deming's suggestion that "the greatest waste in America is the failure to use the abilities of people." He agreed with Deming that the aim of every organization should be for everybody to gain – stockholders, employees, suppliers, customers, community, and the environment – over the long term. [4]

The father of an autistic son, Lewis struggled for years to show that the popular command-and-control management practices embedded in most business systems were discriminatory, inefficient, and barriers to employee engagement and organizational agility. Lewis and his team recognized that accomplishing their aims would require changing perceptions about people with disabilities in the Walgreens workforce, eliminating policies and practices obsoleted by advancing technology, and promoting a culture of inclusiveness. Before Walgreens' Anderson DC, no company had attempted a transformation of such scale. Consequently, the Walgreens team pioneered many steps to transform this new distribution center into a high-performing, people-centric organization.

The journey to success

To accomplish the objectives for the new DC, Walgreens managers studied every aspect of the distribution process, often redesigning jobs and replacing repetitive, tedious, or physical work with technology-driven solutions. Rather than requiring a task to be completed in a predetermined manner, management focused on its desired outcome. In many cases, the changes to make work easier—for example, using touchscreens with pictures and icons, and height-adjustable workstations for people with disabilities—made the work easier and more efficient for everyone. Processes around recruitment, evaluation, and selection of DC employees also changed, becoming more flexible and inclusive. "We didn't lower our productivity standards," explained Deb Russell, Walgreens' manager of outreach and employee service. "Our goal was to work more intuitively." [6]

What we need to do is learn to work in the system, by which I mean that everybody, every team, every platform, every division, every component is there not for individual competitive profit or recognition, but for contribution to the system as a whole on a win-win basis.

— W. Edwards Deming

Many of the machines used in the new DC were custom designed and built by a German specialty manufacturer. After learning that their work would be critical to the employment of people with disabilities, and would ultimately change people's lives, the German company’s workers exceeded all expectations. In Lewis' words, they "transformed from bricklayers to cathedral builders." [5]

Results from the Anderson DC

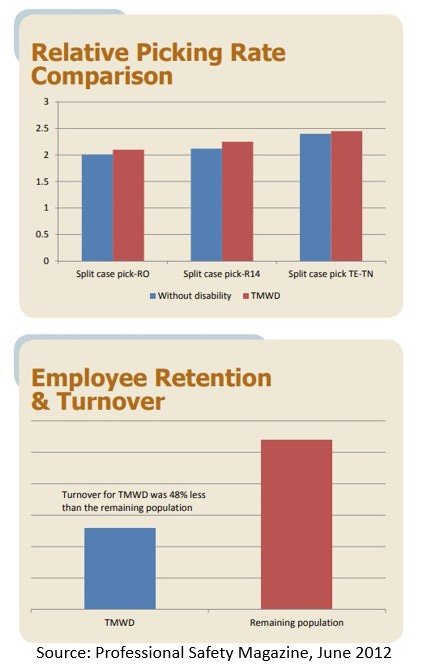

In 2012, Walgreens’s Anderson DC completed its fifth year of operation. At that time, Anderson employees with a disclosed disability made up 37% of the workforce, and the results have been extraordinary by most measures. For example, a peer-reviewed study reported in Professional Safety magazine [7] found that:

Workers with and without disabilities were equally productive.

People with disabilities had significantly lower turnover and absentee rates than non-disabled employees.

Safety incidents-accidents per 1,000 hours were one-third lower for people with disabilities compared to other employees.

While a new facility was the original impetus for this initiative, today all of Walgreens' 21 DCs employs many people with disabilities. Eventually its aim is for people with disabilities to constitute at least 20% of the division's overall workforce, and, following the stunning example set by Walgreens, numerous other Fortune 500 companies are creating similar programs, including Best Buy, Meijer, Lowe's, and Proctor and Gamble.

The aim of leadership should be to improve the performance of man and machine, to improve quality, to increase output, and simultaneously to bring pride of workmanship to people.

— W. Edwards Deming

Final thoughts

Lewis has since retired from Walgreens but continues to promote an inclusive workforce through his book No Greatness Without Goodness and presentations worldwide. Thousands of lives are being transformed through his work, the roots of which lie in his introduction to Deming's belief in the capability of people.

What’s the use of having power if you don’t use it to do good?

— Randy Lewis

In his last interview before death, Deming stated that a manager's job was to give people a chance to make use of their skills, capabilities, and hope—in other words, to help people accomplish their aims. People with or without disabilities simply need to understand their jobs, how their work fits in, and how they can contribute. It is this understanding that then enables them to experience joy in work.

References

Lewis, R. (2014) No Greatness Without Goodness: How a Father’s Love Changed a Company and Sparked a Movement. Tyndale House Publishers, Inc, pp. 99-101.

Moore, J., Hanson, W., Maxey, E. & Kraemer, L.. (2017). Fully Integrated Inclusive Organization: Beyond Accommodations. Academy of Management Proceedings. 2015.

Deming, W. (1982) Out of the Crisis. Reissue The MIT Press, p.53 (October 15, 2018)

Deming, W. (2000 ) The New Economics for Industry, Government, Education. The MIT Press; 2nd edition (August 11, 2000)

Lewis. (2014) p. 105.

Wells, S. (2008) Counting on Workers with Disabilities. HR Magazine. (April 1, 2008)

Kaletta, J., Binks, D. and Robinson, R. (2012) Creating an Inclusive Workplace: Integrating Employees With Disabilities Into a Distribution Center Environment. Professional Safety Magazine. (June 2012)

Deming's suggestion that "the greatest waste in America is the failure to use the abilities of people."

It reminds me one of His favorite quotes:

“I think that people here expect miracles. American managers are morons, They think all they have to do is just copy from Japan, but they don't know what to copy!”

After so long his quote is still valid, just include people from other disciplines and geographies